There has been a great deal of news about how polar bears are suffering due to the lack of sea ice. Now, a research team from Canada and Denmark has found that polar bears are also vulnerable because of environmental toxins.

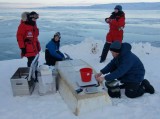

Carleton grad student Alana Greaves was part of the research team that found high levels of per/polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in multiple tissues of polar bears.

PFASs are man-made chemicals that are used primarily in non-stick type applications such as protective coatings on food containers, stain protective coatings on clothing and textiles, lubricants, and fire-fighting foams, among others.

Says Greaves: “For my master’s research, I analyzed the distribution of PFASs in multiple polar bear tissues: liver, blood, muscle, fat, and brain. We found that PFASs were detected in all 12 tissues of the polar bear, including all 8 brain regions, indicating that PFASs are capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier.”

Says Greaves: “For my master’s research, I analyzed the distribution of PFASs in multiple polar bear tissues: liver, blood, muscle, fat, and brain. We found that PFASs were detected in all 12 tissues of the polar bear, including all 8 brain regions, indicating that PFASs are capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier.”

Greaves says these findings are concerning for the bears. “Very little is known about the direct toxicological effects of PFASs in polar bears, although they have been shown to be carcinogenic and/or neurotoxic in lab rodent studies. In particular, PFASs have been found to be tumor promoters, cause abnormal motor neuron development, and alter hormone levels found in the thyroid hormone pathway.”

Greaves says these findings are concerning for the bears. “Very little is known about the direct toxicological effects of PFASs in polar bears, although they have been shown to be carcinogenic and/or neurotoxic in lab rodent studies. In particular, PFASs have been found to be tumor promoters, cause abnormal motor neuron development, and alter hormone levels found in the thyroid hormone pathway.”

Recent studies have also shown that PFASs are also detectable in the brains of harbor seals, harbor porpoises, glaucous gulls, and brown pelicans, among others.

Greaves completed her MSc in Chemistry (with specialization in Chemical and Environmental Toxicology) in 2012, under the direction of adjunct professor Dr. Robert Letcher.

“Doing my master’s with Rob here at Carleton has been wonderful,” shares Greaves. “As a result, I decided to stay with Rob for my doctoral work too.”

She is currently pursuing her PhD in chemical and environmental toxicology. For her PhD, she is looking at a new class of environmental toxins, organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs) that have emerged in the last decade as a replacement to more common-place flame retardants.

“Little is known concerning their environmental levels and metabolism potential,” says Greaves. “My study involves analyzing wildlife species from the Great Lakes. In particular, I am studying the tissue distribution patterns of OPFRs in herring gulls, and looking at how these chemicals get metabolized in both birds, and fish from the Great Lakes area.”

Photos in this story courtesy of R. Dietz and R. Letcher.

Monday, September 9, 2013 in Grad Student Research, News

Share: Twitter, Facebook