Crawford getting ready to leave from Qikiqtarjuaq, NU

Not every graduate student has had their field work thwarted by the presence of a polar bear.

This is just one of the many hazards of researching ice islands in the Canadian Arctic, which is what Carleton PhD student Anna Crawford is currently undertaking.

Crawford is in the process of completing her PhD in Geography in the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies. In 2013, she completed her MSc in Geography in the same department here at Carleton.

“Ice islands are technically a type of iceberg – just an immense and tabular one,” explained Crawford.

“We have seen a number of ice islands in both the eastern and western Canadian Arctic regions recently due to the break-up of ice-shelves on Ellesmere Island (Nunavut) and the floating ice tongues of glaciers in northwest Greenland.”

Crawford studies how these ice islands deteriorate as they drift and she has developed methods to detect this deterioration.

So what’s the best way to study ice islands? By working right on top them of course.

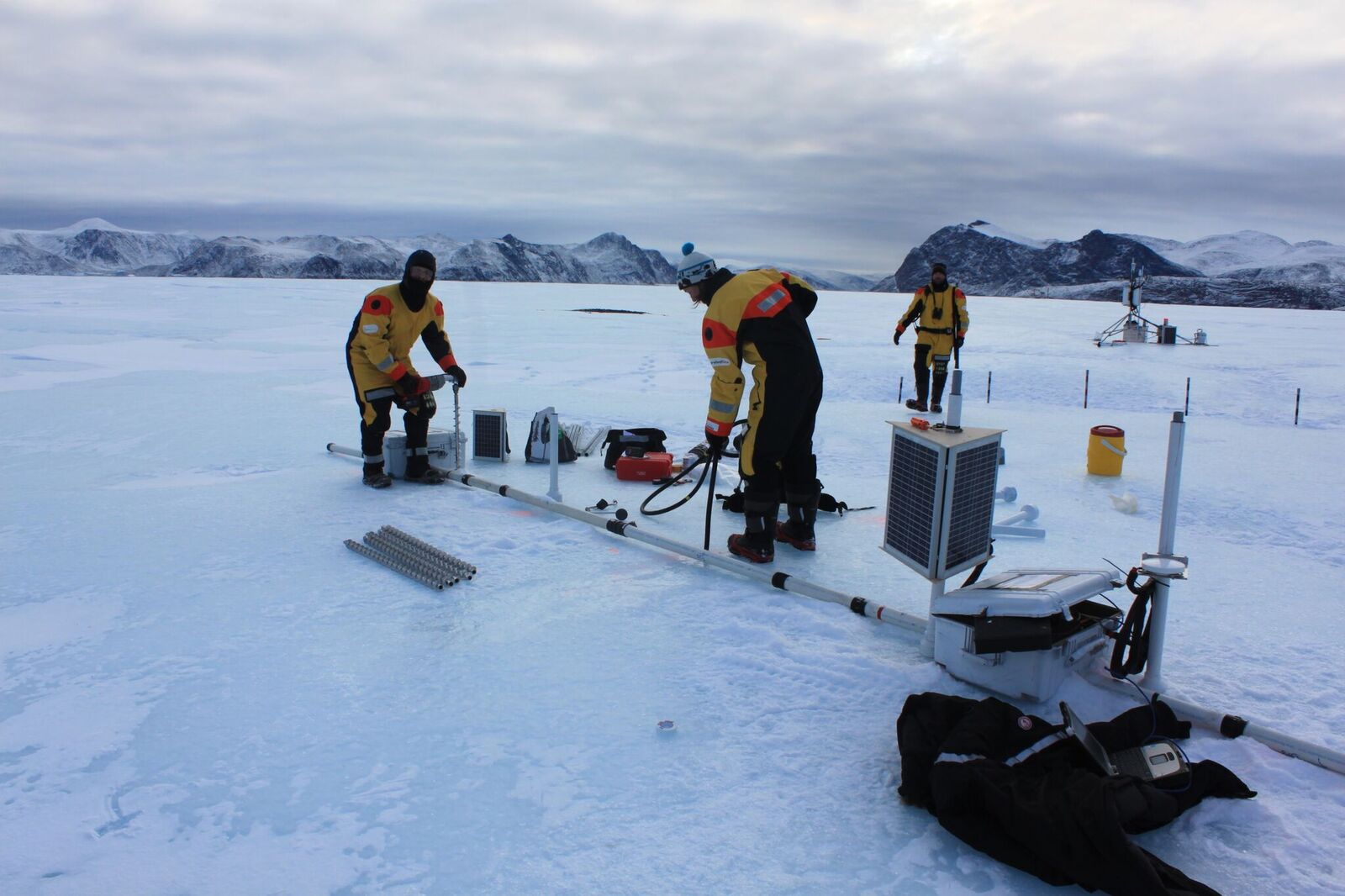

Crawford equips the ice islands with instruments and takes various measurements while on top of the big, flat surfaces.

Preparing the team and helicopter on the CCGS Amundsen for an ice island field work day. Photo credit: Graham Clark

In 2015, she installed an ice penetrating radar system which records and transmits daily ice thickness data, and a small automatic weather station which records environmental data.

Research on ice islands is important within the context of climate change and the danger that the islands pose to ships and infrastructure.

“These areas are changing rapidly. Climate change is modifying the landscape, and industry is more readily operating in the Arctic,” said Crawford.

“Both of these will impact the idealized picture that many of us in the Canadian South have of the Arctic.”

Installing an ice penetrating radar to measure the thickness of an ice island in Baffin Bay. Photo credit: Graham Clark

Climate change is also leading to increased ocean and atmospheric temperatures and decreasing sea ice extents, all which lead to increased chances for ice islands to be created. A large ice island will fracture numerous times, thus generating numerous ice island fragments – all of which are hazards to the aforementioned industry.

Ice islands also deteriorate through melting (via slower processes and similar to an ice cube dissolving in a drink) which inputs fresh water into the ocean.

“This can change the physical, chemical, and/or biological properties of the ocean column, possibly affecting ecosystems and even ocean circulation patterns,” said Crawford.

Crawford has been provided transportation and access to water bodies across the Eastern Canadian Arctic via the CCGS Amundsen, an icebreaker outfitted for science research.

“We stay in bunks and have three square meals a day (plus many delicious snacks in between). Both the science and ship crews are extremely helpful and it feels like quite a team atmosphere when you’re on board,” said Crawford.

“The only thing you have to worry about is going a little stir-crazy after any particularly long cruise leg, or sea-sickness– I can personally say that the Labrador Sea in October is quite exciting.”

The CCGS Amundsen travelling through a fjord on the east coast of Baffin Island

Crawford is thankful that she has been able to go to this region of Canada, and has seen firsthand how and why community members love their home regions.

In 2016, she actually had a “home base” in the town of Qikiqtarjuag, Nunavut – a small community on the east coast of Baffin Island.

“We would snowmobile two hours – one way – over the sea ice to the ice island each day.”

Crawford had a lot of positive things to say about the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies (DGES).

“Derek Mueller, my supervisor, has provided both myself and my other lab mates with an incredible number of opportunities,” said Crawford.

“We often hear of the cut-throat competitiveness of academia, but the DGES has fostered collaboration and cooperation amongst its graduate students.”

You can read more about Crawford’s research on her blog.

Monday, January 30, 2017 in Grad Student Research, News

Share: Twitter, Facebook